I research how human-modified tropical landscapes change behavior, ecology, and community composition.

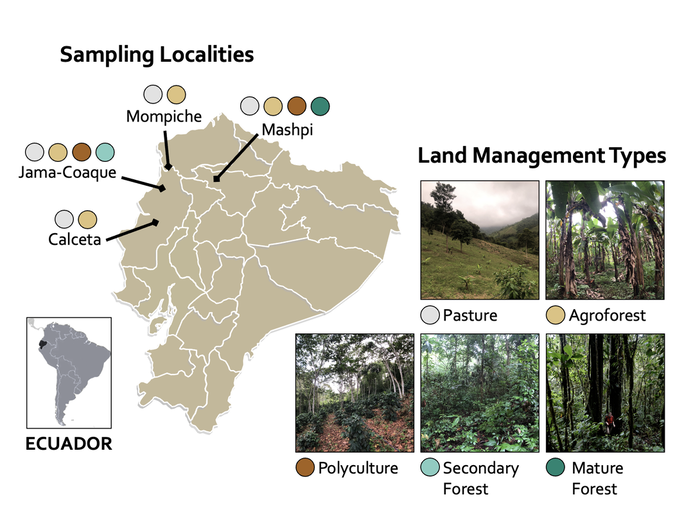

I conduct most of my fieldwork in Ecuador, along a gradient of human disturbance:

As in many tropical countries, the forests of Ecuador are extremely fragmented. At each of my field sites, I compare frog communities in healthy forests, forests in the process of growing back, agricultural areas that still provide vegetation structure & shade (e.g. coffee, cacao, banana) and deforested cow pastures and monocultures (e.g. pineapple). Above, you can see representative photos of each site type.

Some of my research questions are as follows:

How does the soundscape change as habitats become more degraded?

How do these changes affect animals that rely on vocalizations to attract mates?

Can the soundscape help explain why we only find certain animals in certain places?

What types of habitat degradation discourage movement? Disease susceptibility?

Can agroforests like shade-grown coffee or cacao be as beneficial as secondary forest?

How can these agroforests provide a win-win for connectivity and local livelihoods?

How do these changes affect animals that rely on vocalizations to attract mates?

Can the soundscape help explain why we only find certain animals in certain places?

What types of habitat degradation discourage movement? Disease susceptibility?

Can agroforests like shade-grown coffee or cacao be as beneficial as secondary forest?

How can these agroforests provide a win-win for connectivity and local livelihoods?

I pursue answers to these questions with frogs in mind. Why?

1) Frogs are understudied in conservation (historical focus on birds & mammals)

2) Frogs are essential for ecosystem health (e.g. indicator species, role in food webs)

3) Frogs do not learn their calls (which makes studying their communication easier)

4) I love frogs. Especially glass frogs:

2) Frogs are essential for ecosystem health (e.g. indicator species, role in food webs)

3) Frogs do not learn their calls (which makes studying their communication easier)

4) I love frogs. Especially glass frogs:

|

This is Hyalinobatracium mashpi, a new glass frog species that I helped discover with a team of amazing biologists in Ecuador.

This little guy is sitting on a piece of glass–and yes, that's his heart beating! Read about it here! |

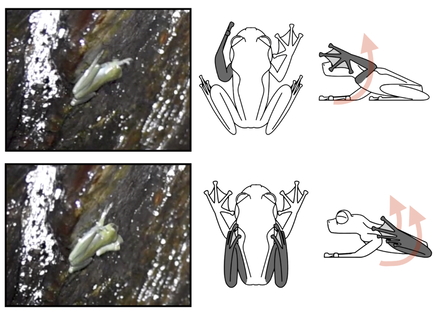

Since I work in remote places, I often come across behaviors

(and sometimes even new species!) that haven't been recorded before.

(and sometimes even new species!) that haven't been recorded before.

Despite centuries of research, nature is still largely a mystery--which is part of what makes it so wonderful. However, to make informed conservation decisions, we need to know as much as possible! So, whenever I can, I also try to describe new insights into the natural history of species: behaviors, breeding biology, vocalizations, diet–you name it.

My favorite discovery thus far...

Sachatamia orejuela is an elusive glass frog species that is only found near roaring waterfalls in Ecuador and Colombia. I recently discovered that because their habitats are so noisy, they use TWO forms of communication to attract a mate: calling and waving their arms & legs. Their call (which I described for the first time in the same paper) is the highest-pitched of any known glass frog, which likely evolved to combat the white noise of the waterfall. Read the paper here!